Natural rumen viruses for sustainable dairying

Why is this research important?

The agri-food sector is vital to Ireland’s economy, but farming is also the country’s largest source of greenhouse gases. A major challenge is cutting emissions while still feeding a growing population. Cows, for example, naturally produce methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, during digestion.

Several solutions are being explored, including feed additives and changes in farm management. Our research focuses on another option: bacteriophages.

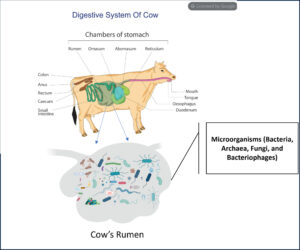

Bacteriophages are tiny viruses that only attack specific bacteria. They are harmless to humans and animals and already exist in the cow’s stomach (the rumen), where microbes break down grass. Some of these microbes produce methane. By using bacteriophages to target methane-producing bacteria, we aim to reduce emissions safely, without affecting cow health or milk production.

What the research tells us?

Inside the cow’s rumen, millions of microbes help break down grass. Bacteria do most of the work, but their by-products feed another group of microbes, called archaea, which then release methane.

We are exploring whether bacteriophages (natural viruses that target only specific microbes), can safely reduce these methane-producing archaea. The goal is to lower emissions while keeping cows healthy. Our work is still at an early stage, but we are already learning a lot about the bacteriophages that could make this possible.

Visual Evidence: A look at bacteriophage in rumen

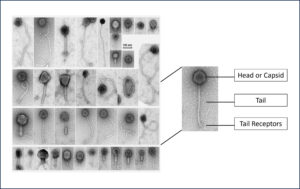

Bacteriophages are far too small to see with the eye or even a normal microscope. To study them, we use an electron microscope, which lets us capture detailed images at the nano-scale.

These images show the remarkable variety of phages inside the cow’s rumen, some with a head for storing genetic material and a tail for attaching to bacteria. Having this clear “picture proof” is key, because it helps us understand which bacteriophages are present and how they might be used to cut methane emissions.

Genetic mapping

An image shows us a phage’s shape, but DNA sequencing reveals its purpose. Every phage carries a unique genetic “instruction manual” that tells us which bacteria it can infect and what functions it may influence. By sequencing entire rumen samples (a process called metagenomics), we can rapidly discover new phages and understand how they might help reduce methane emissions.

Progress so far

Now in its second year, the project has successfully collected and analysed rumen samples, visually confirming a huge diversity of bacteriophages. To date, we have identified around 86,000 unique phage genomes, one of the largest datasets of its kind, providing a major new resource for rumen microbiome research.

Next steps

In the coming year, we will link phages to their bacterial hosts and identify key proteins that determine how they interact. These steps will set the foundation for practical applications aimed at reducing methane emissions in ruminant farming.

Contact details

- PhD student: Naveen Gattuboyena (Naveen.Gattuboyena@teagasc.ie)

- Principal investigator: Dr. John Kenny (John.Kenny@teagasc.ie)

- Academic supervisor: Prof. Jennifer Mahony (UCC)