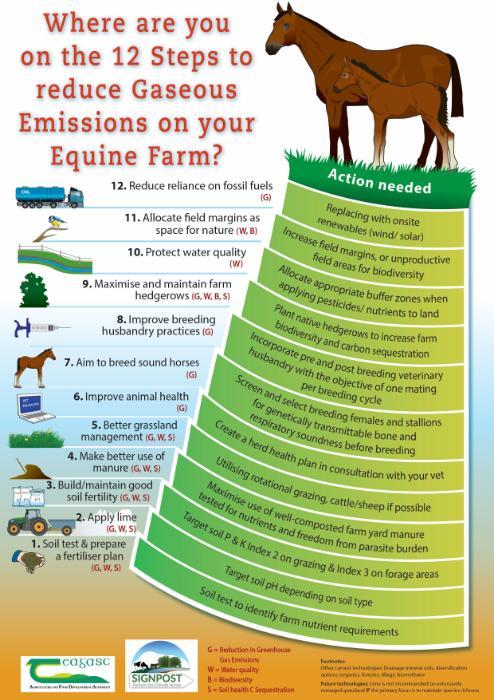

Where are you on the 12 Steps to Reduce Gaseous Emissions on your Equine Farm?

Aspects of environmental sustainability and animal welfare play an important role in the social acceptance of horse husbandry, and breeding. Integrating sustainable practices in horse husbandry not only enhances animal welfare but also contributes to environmental conservation. As an example, providing horses with well-managed grazing areas can promote ecological sustainability while ensuring the well-being of the animals. The following are suggested practices contributing to more sustainable farming.

- Soil test & prepare a fertiliser plan – soil test to identify farm nutrient requirements

Healthy soil with active biological processes is essential for nutrient cycling and making nutrients accessible to plants, while also helping to achieve environmental goals.

Soil sampling is a crucial step in understanding soil nutrient needs, and soil analysis determines the fertility levels of key nutrients such as lime, phosphorous (P) and potassium (K). Knowing the soil fertility on a field-by-field basis is the first step to calculating fertiliser (including lime) requirements, and managing fertiliser costs. For accurate results, soil samples should be taken from the top 10cm of soil, in a W pattern, avoiding areas like gateways or latrines. A minimum of 20 cores per 2-4 hectares should be collected, and sampling should not occur within three to six months after applying phosphorous (P) or potassium (K ), or within two years of the last lime application. The results from soil testing are the foundation for creating a fertiliser plan with the help of your agricultural advisor.

- Apply Lime – target pH of 6.3 to 6.5 on mineral soils & 5.5 to 5.8 on peaty soils

For optimal grass production aim for pH of 6.3 to 6.5 on mineral soils and 5.5 to 5.8 on peaty soils. This is crucial for nutrient availability (N, P, & K) and will enhance grass productivity each year.

Lime application guidelines include:

- The maximum single application is 7.5t/ha with the remaining lime applied two years later.

- Avoid over-liming soils, as this can reduce nutrient availability, particularly phosphorous (P).

- Lime can be applied at any time of the year, but it’s most effective when applied to low grass covers (e.g. after grazing or cutting, or to prevent residue build-up).

- Maintaining soil pH helps release nitrogen (up to 70kgN/ha) from organic matter in the spring which supports early season growth.

- For soils with high molybdenum (Mo) levels, maintain a pH below 6.2 to reduce problems with copper deficiency. Alternatively, follow lime recommendations and supplement animals with copper.

- High molybdenum levels can interfere with calcium, phosphorous, and copper utilisation, all essential for healthy development.

- For heavier and organic soils, apply lower rates (< 5t/ha), more regularly to avoid ‘softening’ the soil and to reduce the risk of poaching

For those interested in maintaining, or being compensated for maintaining low-input permanent pasture, the restricted use of fertilisers including lime, and restricted use of pesticides promotes a more diverse sward, which benefits both flora and fauna.

- Build/maintain good soil fertility – Target soil Phosphorous (P) and Potassium (K) index 2 on grazing, and index 3 on forage areas

The Nitrates Action Plan regulations (March 2022) specify that the “phosphorous (P) index for soil shall be deemed to be Index 4 unless soil test indicates a different P index is appropriate in relation to that soil”. This means that no phosphorous (P) chemical fertiliser can be applied without prior soil testing, with tests no more than four years apart. Applying fertiliser without soil test data is like making decisions blindly.

For productive ryegrass swards, the goal is to achieve P and K Index of 3. Maximising grass production on haylage and hay areas is important for both yield and quality. However, for grazing areas used by equines, this may not be necessary due to lower grass demand. Maintaining a P & K Index of 2 may be sufficient for more extensively grazed farms/lower stocking densities of equines, depending on grass production requirements.

Table 1: Soil Phosphorous and Potassium Index Systems explained:

| Soil P & K Index | Soil P (mg/l) Grassland | Soil K (mg/l) Grassland and Other Crops |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0 – 3.0 | 0 – 50 |

| 2 | 3.1 – 5.0 | 51 – 100 |

| 3 | 5.1 – 8.0 | 101 – 150 |

| 4 | > 8.0 | > 151 |

Table 2: Maintenance (Index 3) N, P and K advice at different stocking rates (equine livestock unit/ hectare):

| Stocking Rate (SR) | N (kg/ha)* | P (kg/ha) | K (kg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25-40 | 3 | 4 |

| 1.5 | 25-40 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | 25-40 | 6 | 8 |

*Apply 25kgN/ha in springtime. Apply additional N based on grass demand during the growing season

Apply fertiliser when soil and weather conditions are appropriate, when soils are at above 5°C, conditions allow machinery to work without damaging the soil structure, and there is a forecast of 48 hours of dry weather after application (check Met Éireann in advance).

- Make better use of farmyard manure (FYM) – maximise use of well-composted FYM tested for nutrients and freedom from parasite burden

Horse owners must decide whether to retain farmyard manure on their property or export it. This decision includes considering the composting system, its duration, and effectiveness. It is also important to take into account whether there is any anthelmintic resistance on the farm (in which case all FYM should be exported), and the amount of land available for spreading composted FYM on, while ensuring land is rested after application before grazing.

Composted manure offers several benefits for soil improvement:

- Improves water holding capacity, especially in light soils which can help reduce flooding

- Increased soil microbe population and diversity, enhancing aeration in heavy soil

- Provides essential nutrients (N, P, K and micronutrients) that benefit the soil, reducing the need for artificial fertilisers and releasing nutrients slowly over time period, unlike chemical fertilisers

- Increases the humus content of the soil

- Can promote more even grazing

Well-rotted farmyard manure can be effectively used on grazing areas for horses. However, to ensure effective composting, the manure pile must reach temperatures above 40°C, and regular turning is required to introduce air and promote even composting. Some composting systems also incorporate water or air injection to enhance the process.

Applying 25 tonnes per hectare (10 tonnes per acre) can be beneficial, particularly for areas of the farm used for haylage or hay production. FYM composition can vary significantly depending on its source and storage, so it’s important to test it to determine its nutrient value. Where available, cattle or pig slurry can also be used.

- Better grassland management – utilising rotational grazing, cattle/sheep if possible

Mixed grazing with cattle or sheep is beneficial for managing grass supply and maintaining an even sward, as they graze areas that horses leave behind. Sheep cause less damage and poaching than cattle during wet periods and typically leave the turf in a more uniform condition, although it’s important to ensure the fencing is suitable.

Sheep or cattle can be grazed after horses to help manage ungrazed areas of paddocks. Cattle are more likely to graze longer grass and can sometimes be followed by horses. However, caution is needed if high fertiliser inputs are used to maintain cattle, as this could pose health risks to horses.

Grazing with cattle or sheep also helps reduce the build-up of parasite larvae and eggs on pasture, interrupting the life cycle of equine internal parasites. Sheep are particularly effective for early winter grazing before closing paddocks for spring growth. Resting paddocks between grazing periods is important for sward recovery and can further assist in parasite control.

- Improve animal health – create a herd health plan in consultation with your vet

In addition to the financial burden of poor health, there is also an environmental cost associated with the use of drugs and medicines to manage illness. Effective health management reduces the need for antibiotics, lowers veterinary expenses, and helps prevent decreased performance (athletic or reproductive). Strategies for improving health also involve optimising feeding practices and minimising feed waste.

Taking a proactive approach to disease prevention, rather than relying solely on treatment, is more sustainable for health, welfare, and the environment. Following recommended vaccination protocols, conducting regular health monitoring, and maintaining good biosecurity practices help reduce production and performance losses, lower veterinary costs, enhance animal welfare, and increase equine longevity.

- Aim to breed sound horses – screen and select breeding females for genetically transmittable bone and respiratory soundness before breeding. Stallions likewise.

Screening for genetically inherited unsoundness to inform breeding decisions reduces the risk of passing on defects, supports individual welfare, and minimises the need for veterinary interventions and medical treatments. Selecting for improved longevity and better survival rates leads to higher-performing equines, while promoting more socially responsible and economically sustainable breeding practices.

- Improve breeding husbandry practices – incorporate pre and post (before and after) breeding veterinary husbandry with the objective of one mating per breeding cycle

Reducing the number of matings per cycle while simultaneously placing focus on reproductive fertility indicators, has a direct impact on sustainability in the context of reducing the foaling interval and improving reproductive efficiency, also a key component of economic sustainability.

- Maximise and maintain farm hedgerows – plant native hedgerows to increase farm biodiversity and carbon sequestration

Hedgerows play an important role in sequestering carbon by storing it in woody growth, roots, leaf litter, and soil organic matter. While newly planted hedgerows offer the greatest potential for carbon sequestration, allowing hedgerows to grow one meter outward and upward can also increase carbon capture by one to two tons per hectare per year. Native trees and shrubs are especially valuable for heritage and biodiversity. In addition to carbon storage, hedgerows provide habitats for pollinators, plants, and wildlife, help prevent soil erosion, intercept water flows, and offer shelter and stock-proofing.

- Protect water quality – allocate appropriate buffer zones when applying pesticides/ nutrients to land.

Protecting water sources (such as drains, watercourses, streams, lakes, wells, and abstraction points) from nutrient, sediment, and pesticide runoff is a key aspect of Nitrates regulations. When applying fertilisers, cultivating, or spraying fields, it is important to consider buffer zones to reduce nutrient loss, sediment, and pesticide runoff, and to disrupt the flow of surface runoff. A riparian buffer zone is an area adjacent to a water body where no chemical and organic fertilisers, cultivation and spraying can be carried out. Zones vary in width tailored to the specific landscape and water bodies they protect.

Runoff is most likely when soils are waterlogged, with excess rainfall causing fertilisers, chemicals, and sediment to be carried over the surface. In fields with poorer drainage, widening buffer zones enhances water protection. Natural vegetation or native wooded or scrubby buffer zones help absorb nutrients, trap sediment, and improve water infiltration, while also supporting biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and riverbank stability. Your local ASSAP advisor can provide free guidance on the appropriate location and size of riparian buffers for your farm.

https://www.teagasc.ie/environment/water-quality/farming-for-water-quality-assap/people/

- Allocate field margins as space for nature – increase field margins, or unproductive field areas for biodiversity

Field margins are strips of naturally growing vegetation along the edges of fields, adjacent to linear features like hedgerows. They serve as vital habitats and ecological networks, supporting biodiversity and providing essential resources for various species.

Management Guidelines for Field Margins:

- Protect field margins by fencing them off from livestock to preserve their ecological integrity.

- To prevent vegetation from becoming rank or transitioning into scrub, cut field margins in autumn after plants have flowered. Aim to mow at least once every three years.

- Maintain a minimum of 1.5 meters between the main field crop and the base of the field margin when spraying, cultivating, or applying fertiliser. Wider margins can reduce the need for chemical sprays, as the space allows for mechanical hedge cutter control of any encroachment.

- Refrain from blanket spraying, as this practice can lead to the removal of plant diversity within the margins.

- Do not apply chemical fertilisers, slurry, manure, or lime within field margins to prevent nutrient enrichment and maintain ecological balance.

- There is no need to sow seed mixes within margins, as natural regeneration often supports local biodiversity effectively.

By adhering to these management practices, field margins can be maintained as effective ecological features, enhancing biodiversity and supporting sustainable farming practices.

- Reduce reliance on fossil fuels – replacing with onsite renewables (wind/solar)

Integrating renewable energy sources such as wind, and solar, can diversify income streams, support sustainable energy production, and offer long-term economic benefits. However, it is crucial to conduct careful planning, understand regulations – including permits, grid connection requirements, environmental impact assessments, and planning permission – and perform comprehensive financial evaluations before initiating renewable energy projects. By carefully considering these factors equine owners can make informed decisions about incorporating renewable energy into their enterprises, leading to both environmental benefits and economic resilience.